Southeast Asian Strategies toward the Great Powers: Still Hedging after All These Years?

Over the past two decades, our understanding of how the relatively small states of Southeast Asia engage in great power management has grown significantly. The tendency during the early 1990s to view Southeast Asian policymakers as having “no strategy” has been replaced by a small industry of scholars and analysts explicating Southeast Asian strategies towards the great powers. By the mid-2000s, they had introduced into the wider literature three key ideas. First, there was strategic thinking behind the political and security policies of key Southeast Asian states vis-à-vis great powers, even though they might not fall neatly into the categories common to International Relations (IR) theory, such as balancing or bandwagoning. Second, while there were variations in individual Southeast Asian states’ strategic preferences and behaviour, the shared pattern in their aspirations was of “hedging” or not overtly choosing sides. This entailed engaging China and trying to socialize it as a responsible great power, while helping to sustain US forward deployment and military deterrence in the region. Third, because these strategic efforts centered on managing uncertainty, their effectiveness and durability would have to be continually evaluated.

Since 2009-2010, apparent changes in Southeast Asian alignment inclinations have resulted from China’s more assertive approach to maritime territorial disputes, leadership changes in several key neighboring countries, and the Obama administration’s rebalance to Asia. The security dilemma has intensified over the multi-nationally disputed islands, atolls, and rocks in the South China Sea (SCS), despite initial commitment by Beijing and ASEAN to its multilateral management. Apart from quietly signing a bilateral agreement in 2004 with Manila for joint survey of oil and gas resources around the Spratlys that undermined the multilateral 2002 Declaration of Conduct, China also opposed ASEAN members’ practice of consulting among themselves ahead of negotiations. In 2010, Southeast Asian officials were further disquieted by reports of Chinese officials calling the SCS one of China’s “core national sovereignty interests.” Since then, Chinese vessels have cut the cables of Southeast Asian oil exploration vessels; China and the Philippines had a two-month stand-off over Scarborough Shoal in 2012; China ostentatiously placed a giant oil rig within Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in mid-2014; and it began reclamation and construction work on several atolls in 2015. In response, Manila and Hanoi have harnessed international support to criticize China’s actions, and stepped up their security partnerships with the United States and its allies. The Philippines is also awaiting an International Court of Arbitration ruling on its case against China.

By themselves, these developments might have had limited impact on the wider international order, insofar as it is generally understood that neither the United States nor China is eager to risk war with each other over the SCS territorial disputes.1 However, Hanoi and Manila’s turn to Washington for strategic reassurance in 2010 coincided with already rising US concerns after Chinese ships harassed the navy surveillance ship Impeccable in the SCS in March 2009; China’s reluctance to condemn North Korea after the sinking of the Cheonan in March 2010; and the discovery of a new Chinese underground nuclear submarine base on Hainan Island facing the SCS. The Obama administration’s 2011 rebalance to Asia also coincided with escalating Sino-Japanese tensions after a Japanese coast guard vessel collided with a Chinese fishing trawler in late 2010; the Chinese government aggressively responded to the Japanese government’s 2012 purchase of three of the disputed Senkaku Islands; and Beijing in 2013 declared an Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) over parts of the East China Sea.

Thus, over the last five years, the Southeast Asian landscape has increasingly resembled realist predictions of power balancing in the form of growing security cooperation with the aim of countervailing the greatest perceived threat China. In light of this trend, is the claim about Southeast Asian “hedging” vis-à-vis the United States and China still relevant, or ought we to adjust our interpretation of their alignment choices?

Hedging within the Spectrum of Southeast Asian Great Power Strategies

In the context of positioning between the United States and China, if we were to plot along a spectrum the relative extent to which Southeast Asian states privilege their alignment choices vis-à-vis these two great powers, “hedging” intuitively refers to the middle range. One of the most widely used definitions of Southeast Asian hedging is “a set of strategies aimed at avoiding (or planning for contingencies in) a situation in which states cannot decide upon more straightforward alternatives such as balancing, bandwagoning or neutrality. Instead, they cultivate a middle position that forestalls or avoids having to choose one side at the obvious expense of another.”2 This is a definition specific to what I shall call “triangular hedging,” which entails a trade-off, usually in the form of a zero-sum alignment choice, to be made between one great power and the other.3 This type of hedging is, at heart, “a class of behaviours which signal ambiguity regarding great power alignment.”4 By this tighter understanding of triangular hedging, countries that are already treaty allies with one of the two great powers cannot really be said to be hedging, and stronger hedgers are those that achieve greater degrees of ambiguity in relative alignments. To facilitate comparison, we may identify three basic groups of Southeast Asian states according to their alignment behavior and options circa the mid-2000s.

The US allies

The Philippines and Thailand, the only two states in the sub-region that are formally aligned. The Philippines has had a Mutual Defense Treaty with the United States since 1951 and hosted large US bases for over 40 years after World War II. A new Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) in 1999 allowed the United States to resume ship visits and conduct large military exercises with Philippine forces, and from 2002 US combat forces were deployed to support Filipino troops fighting an insurgency in Mindanao. Thailand’s US alliance is underpinned by the 1954 Manila Pact and 1962 Rusk-Thanat communiqué. Thailand provided vital basing for US forces during the Vietnam War, and it continued to play an important post-Cold War role in US wars in the Middle East and Afghanistan, and regional disaster relief operations. Both countries were designated US “major non-NATO allies” during the early years of the “Global War on Terror” (GWOT), granting them access to more US military assistance, equipment, and aid. While both actively engage and have military-to-military ties with China, their formal alignment with Washington entails rights and obligations in times of armed conflict, including conflict with China.

The China-constrained

These are countries whose security strategies prioritize the central role of China: Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnamㅡthe Indochinese states still governed by communist rulersㅡand Myanmar and whose military regime was sanctioned by western countries post-1988. This group is defined by close proximity to China, especially the contiguous states, Vietnam, Myanmar, and Laos. The smallest states (Cambodia and Laos) are also embedded within continental geopolitics involving the competing influences of the sub-regional powers (Thailand and Vietnam), and regard China as a welcome third-party balancer. The so-called ‘CLMV’ area has often appeared to gravitate towards Chinese influence also because of strategic opportunity, or the lack thereof, especially in the case of Vietnam and Myanmar. As Thailand’s experience shows, a continental Southeast Asian state with a history of sub-regional domination and nimble diplomacy may, nevertheless, manage to mitigate the Chinese sphere of influence to a significant extent.

The“hedgers”

Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore most clearly fulfil the requirements to be identified as hedgers. They have neither treaty alliances nor ideological allegiances; they possess viable military-to-military ties with both the United States and China that may be deepened or reduced as needed; and each has overtly pursued “balanced” political-economic ties with both great powers.

All four countries help facilitate US forward deployment in the region as indirect balancing against China. Singapore has been most active since stepping in after the closure of US bases in the Philippines in 1992 to host a naval logistics command center. It allows American access to airbase facilities and opened a naval base in 2001 capable of berthing US aircraft carriers. As part of its support for the GWOT, Singapore signed a new Strategic Framework Agreement with the United States in 2005, allowing expansion of bilateral cooperation in counter-terrorism, counter-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, joint military exercises and training, policy dialogues, and defense technology. Malaysia offers US forces port calls, ship repair facilities, jungle warfare facilities, and low-visibility naval and air exercises. Indonesia’s defense relations with the United States were cut off after the Indonesian military’s involvement in the massacre of civilians in East Timor in 1991, but after their partial restoration in 2005, Indonesia has regularly hosted visiting US naval vessels and the Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI) has been anxious to access US assistance and defense technology. All four countries were founding members in 1995 of the annual Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training (CARAT) military exercises with the US navy; and Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia also participate in Cobra Gold in Thailand, the largest annual US-led military exercise in the Asia-Pacific.

All four countries also engage China significantly, including military-to-military exchanges with Beijing, which also signed a “strategic partnership” agreement with Indonesia in April 2005, facilitating an annual defense dialogue, ministerial visits, and port calls. Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia, which have SCS territorial claims that overlap with China’s, either do not officially acknowledge these disputes, or deal with them in a very quiet manner. Indonesia has tried repeatedly to mediate a multilateral agreement between ASEAN and China, while Singapore keeps its distance as a non-claimant. In view of their domestic racial sensitivities, Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia also have to manage various costly risks associated with their growing socio-economic entwinements with China, including issues of Chinese investments in strategic industries, Chinese migrant workers and students, and returns on state-sponsored economic projects in China.5 Finally, as part of their long-term insurance policy of socializing China, these hedger states all support efforts to enmesh China within regional institutions, though they may differ on whether other great powers should be included.6

Changes over the Last Decade

The past decade is marked by regional states’ responses to China’s maritime assertiveness after 2009 and the US rebalance to Asia after 2011. There has been significant growth in behavior that is often associated with balancing: increased military expenditures; defense postures reoriented towards a key external threat; broadening and deepening of alliance relationships; and the pursuit of more targeted external security cooperation, military assistance, and support for defense capability development.

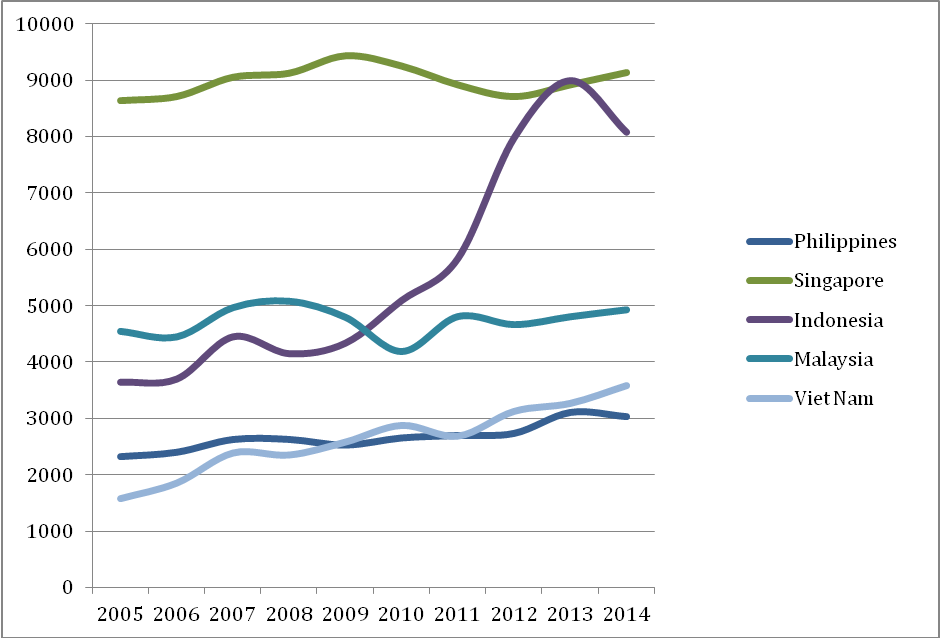

Over a period of general decline in military spending in other parts of the world, total Southeast Asian defense spending grew by 45 percent between 2005 and 2014.The biggest gains were in Vietnam (128 percent) and Indonesia (122 percent), while Philippines expenditures rose by a third. From 2009 to 2014, Indonesia increased its military expenditures by 86 percent and Vietnam by 39 percent.7 Claims of an “arms race” in the sub-region are probably overstated: these growth figures partly reflect these economies’ recovering purchasing power following the 1997 Asian financial crisis; and most of their armed forcesㅡwith the exception of Singapore’sㅡare modernizing from a relatively low base and decades of stagnation. Of specific interest for our purposes, though, these acquisitionsㅡespecially by the maritime countriesㅡare mainly targeted at patrolling territorial waters and defending EEZ against the growing perceived threats from China.

Chart 1. Military expenditures of selected Southeast Asian countries, 2005-2014,

in constant USD billion (2011)

Against this background, how have the strategic choices of the three categories of Southeast Asian states changed over the last decade, with what effect on their relative positioning between the United States and China?

US allies

Over the past decade, a pronounced divergence has grown between the two US treaty allies. Thailand has experienced something of a strategic limbo vis-à-vis the United States because of military coups in 2006 and 2014 and the associated domestic political unrest. In contrast, the Philippines moved to leverage overtly the US alliance in resisting Chinese maritime assertiveness. Over the last five years, the Benigno Aquino administration has committed funds to military modernization, deepened the US alliance, and cultivated defense ties with other US allies.

The Philippines has made several notable arms acquisitions in recent years: two retired US Coast Guard Hamilton-class cutters refitted to be Philippine Navy frigates; two (out of a dozen ordered) FA-50 light fighter jets from South Korea; and two strategic sealift vessels from Indonesia. It has received 4 patrol boats from the United States and purchased 10 high-speed coast guard patrol boats from Japan. Japan is also transferring used patrol planes with basic surveillance radar to the Philippine Navy, and has promised P-3C Orion reconnaissance planes.8 While its aim of achieving “minimum credible defense” will be a long-term and painstaking project, the qualitative changes in Manila’s strategic alignment behavior are more significant.

In the early 2000s, it had rebuilt its US alliance on the basis of anti-terrorism and counter-insurgency, using existing frameworks like the VFA and the annual Balikatan joint exercises. In contrast, its post-2010 alliance strengthening has taken place against a climate of urgency, indignant nationalism, and uncommon consensus on the part of Filipino leaders against Chinese assertiveness; and the US rebalance, designed to convey refocused superpower attention on China’s behavior in Asia. Washington’s stance that the SCS territorial disputes should be resolved according to international law and its repeated affirmations of the bilateral alliance are read in Beijing as having “emboldened” the Philippines to militarize as well as internationalize the conflict.

This revitalized Philippines-US alignment is focused on developing capabilities specific to countering Chinese incursions and defending Filipino claims in the SCS, even though the equipment transferred may be far from the most advanced. It also includes maritime joint exercises such as CARAT, the Philippines component of which is more often than not conducted at SCS locations such as Subic Bay or Palawan.9 The 2011 and 2015 CARAT exercises in Palawan notably featured three US guided missile destroyers and a US littoral combat ship respectively. The latter was immediately followed by an historic joint search and rescue operation between the Philippine and Japanese navies in the same location.10

The US-Philippines alliance strengthening has also been codified in new instruments, especially the 2014 Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), by which the Philippines can resume hosting large rotational deployments of US forces for the next decade.11 As part of the US rebalance, the Philippines has already seen more rotational US deployments after the two sides agreed in 2012 that US forces would re-use facilities at their former bases.12 The key prospect is renewed longer-term US access to the deep harbors at Subic Bayㅡonly 145 nautical miles from Scarborough Shoal, seized by China in 2012, and less than 200 nautical miles from the new Chinese features constructed in 2015ㅡas a more efficient base for SCS operations than the bases in Japan or Guam it is currently using. Manila has also begun negotiating a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) and a VFA to allow the Japanese military to use bases in the Philippines for refueling and supplies, thus extending its patrol range deeper into the SCS.13 The Philippine Senate also ratified a SOFA with Australia in 2012 after a five-year delay.14 These moves to reopen bases to foreign forces are an important indication that over the last five years, Manila has felt sufficiently threatened to have had to make an increasingly clear trade-off between autonomy and alignment. As seen

in repeated bouts of Senate opposition to these measures, and as was evident even at the height of the Cold War, this has by no means ever been an easy choice for the Philippines.

The hedgers

While they have not deviated from an overall long-term hedging strategy, many of the hedgers have intensified elements of their insurance policies to deter Chinese aggression in the short term. Notably, Singapore has extended clear support for the US rebalance. Apart from the rotational deployment of 2,500 marines in northern Australia, the element of the military rebalance most directed at the SCS involves basing up to four new US Navy littoral combat shipsㅡvessels developed for rapid reaction in coastal watersㅡin Singapore. Additionally, an enhanced bilateral Defence Cooperation Agreement was announced alongside the deployment of P-8 Poseidon aircraft from the island in December 2015. In combination with existing P-8 staging points in Japan, the Philippines, and Malaysia, this will facilitate the southern portion of the US maritime air surveillance and anti-submarine coverage in the SCS. To support continued American political-economic leadership in the Asia-Pacific, Singapore officials have also publicly urged US leaders to push through the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal as a crucial complement to its military preponderance.15

Indonesia and Malaysia have adopted renewed maritime foci in their ongoing military modernization to manage growing risks of maritime disputes with China.16 As bilateral security cooperation with the United States recovered after 2008, Indonesia has been negotiating major defense purchases, including 30 F-16 aircraft (including spare parts and pilot training) and 17 The Indonesian and US navies held two exercises in 2015 at Batam Island, near the resource-rich Natuna islands located within China’s nine dashed-lines.18 Indonesia also signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) for defense partnership with Japan in 2015, allowing the transfer of certain Japanese-manufactured equipment and “joint research and production” between their defense industries. Jakarta has reportedly requested radar systems and patrol ships from Japan.19 They have also launched a Japan-Indonesia maritime forum focused on maritime security and a “two plus two” joint defense and foreign ministers dialogue in December 2015, the first for Japan with an ASEAN country.

Malaysia keeps an exceedingly low profile on its security cooperation with the United Statesㅡfor example, it did not become a full participant at the Cobra Gold exercises until 2011, and it has denied publicly that US P-8 aircraft are allowed to fly from its territory despite US sources to the contrary.20 Yet, in recent years Malaysia has moved away from keeping the same very low profile on its territorial disputes with China. Since 2013, its officials have publicly discussed Chinese encroachment into Malaysian waters in an unprecedented manner. For example, in June 2015, they announced the intrusion of a Chinese Coast Guard ship into Malaysian waters at South Luconia Shoals, 84 nautical miles off the Sarawak coast and southwest of the Spratlys. This was followed by leadership-level diplomatic protests, and stepped-up Malaysian patrols in the area,21 echoing the newly-elected Jokowi administration’s public sinking of illegal foreign fishing vessels, many Chinese, caught within Indonesian waters in 2015. Furthermore, as ASEAN chair in 2015, Malaysia facilitated criticism of land reclamation activities in the SCS in the Foreign Ministers Meeting joint statement, and also allowed the ASEAN Defense Ministers meeting to end without a joint statement, deliberately reflecting the open split regarding the SCS disputes.22

Nevertheless, none of the hedgers has deviated from their long-standing deep engagement with China, and each has grasped opportunities to benefit from China’s growth. They have supported China’s Maritime Silk Route, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and membership in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Unencumbered by territorial disputes, Singapore has maintained close working relations with China despite its stronger leaning towards the United States. But the other hedgers also sought deeper partnerships with China after 2010, precisely because of their rising concerns over Chinese maritime intentions. Brunei agreed to undertake joint development in the SCS with Beijing in 2013ㅡthe only claimant to have such an agreement currently. In the same year, Malaysia and Indonesia signed comprehensive strategic partnerships with China, both committing to make progress in security cooperation, an area they had not previously prioritized. Malaysia started regular bilateral defense and security talks with China in 2012, joining Singapore (since 2008) and followed by Indonesia (since 2013).23

As Kuik observes, the timing of these developments reflects a “pragmatic judgment” specific to hedgers, to insure against “all forms of security risks”.24 Thus, Malaysia and, to a lesser extent, Indonesia have tried to manage China’s assertiveness not only by signaling their ability to increase security cooperation with other great powers, but also by generally improving their relationships with China itself. Notably, both have tried to create different dynamics in sensitive maritime zones through constructive defense engagement with China. In 2013-2014, Indonesia held joint naval exercises with China in the SCS, and invited Chinese participation in the humanitarian disaster relief section of the multilateral Komodo exercises around the Natuna islands.25 In September 2015, Malaysia conducted its first joint military exercise with China in the Malacca Straits and surrounding waters; covering joint escort, search and rescue, and humanitarian rescue and disaster relief, it was the largest bilateral military exercise between China and an ASEAN country to date.26

Yet, these episodes are selective, ad hoc, and limited: the point of hedging is to send mixed signalsㅡwhether intentionally, or as a result of policy incoherenceㅡthus, generating ambiguity vis-à-vis relative alignment. For instance, despite cooperation in earlier years, in 2016 the Indonesian navy declined suggestions from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of joint drills with ASEAN states in the SCS.27 We may expect similar limits to its security partnership with the United States too: with its priority on “keep[ing] its options open”, Jakarta “lacks the strategic imperative to greatly deepen cooperation” with either side.28

The China-constrained states

Of the four China-constrained countries, twoㅡVietnam since 2009/2010 and Myanmar since 2011/2012ㅡhave managed to create previously unfeasible political and security ties with the United States and its allies, so as to move along the spectrum toward joining the hedging states. They still feel the China constraint acutely, but their ability to signal ambiguity in alignment intentions towards the United States has increased.

Of the Southeast Asian states, Vietnam has demonstrated the most significant alteration in its strategic posture In 2005, I observed, “Hanoi lacks external strategic partners that can offer the option of more active balancing against China. The United States is the obvious potential partner, but [the communist] Vietnamese leaders have deep reservations about creating a closer strategic relationship…This perception is supported by the invasion of Iraq, and the Bush administration’s declared aim of spreading democracy around the world to ensure US security.”29 Since then, the relationship has gradually improved: they held the first bilateral summit-level strategic dialogue on China and regional security in mid-2005, and have held annual strategic dialogues since 2008, and defense policy dialogues since 2010. The two conducted their first bilateral joint military exercise in 2010 and signed a comprehensive partnership in July 2013.

While some of these developments arose from the gradual post-normalization recovery of Vietnam-US relations, Hanoi has been increasingly concerned about Chinese maritime assertiveness. In 2010, when it used its position as chair of ASEAN to “internationalize” the SCS disputes, Hanoi also successfully lobbied Washington to make strong public statements on them. At the same time, Vietnam began rearming after years of neglect, prioritizing naval spending, including its highly-publicized purchase of six kilo-class submarines from Russia, the first of which are reportedly involved in patrolling the SCS.30 The navy is also acquiring a substantial fleet of surface combatants and patrol and attack aircraft, and building large patrol vessels.31

Over the last two years, Hanoi has also executed tactical political maneuvers to flex its US alignment option in the face of pressure from Beijing. At the height of the oilrig crisis in May 2014, it joined the US-led Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI). Two months later, a pro-China Politburo member visited the State Department without the customary prior visit to China, and extended the invitation for the first visit to Hanoi by a US chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff since the Vietnam War.32 In late 2014, Washington eased existing arms sanctions to allow sales to Vietnam of maritime surveillance and lethal maritime security capabilities on a case-by-case basis. It has also overcome some serious ideological obstacles: in June 2015 their defense ministers issued a joint vision statement, mentioning mutual respect for each other’s political system, and in the following month the Vietnamese Communist Party general secretary conducted what was, in effect, a state visit to Washington.33 Like Indonesia and the Philippines, Vietnam has also sought Japanese assistance in developing its coast guard and surveillance capabilities. Since upgrading their strategic partnership in March 2014, Japan has promised Vietnam patrol vessels, including radar and training.34

Yet, Vietnam remains far from being an exclusive emerging security partner of the United Statesㅡit retains deliberately intimate political, economic, and military ties with China, which it has worked harder than any other Southeast Asian country to keep at an even keel. In 2010, even while Hanoi sought US authority to pressure China over the SCS disputes, Vietnam and China held five confidential meetings to discuss principles for settling maritime disputes, and inaugurated a bilateral Strategic Defence and Security Dialogue.35 Even during the 2014 oilrig crisis, Hanoi and Beijing eventually deescalated by conducting conflict management and resolution talks using the trusted mechanism of the bilateral Joint Steering Committee, in addition to dialogues across the party and military levels. In between there were substantive “party-to-party” and “military-to-military” talks.36

Unlike Manila’s strategy of directly leveraging the US alliance, Vietnam’s strategy of self-help involves developing US military ties as much to express its autonomy as to temporarily offset Chinese power. Consider the limits placed on defence ties with the United States: American warships are allowed just one port visit per year, and no US warships are allowed in Cam Ranh Bay (in particular contrast to Russian warships, which are given preferential treatment). Indeed, Hanoi seemed to have stressed its strategic autonomy in allowing refuelling at the bay of Russian strikers that controversially circled US military installations on Guam in 2015.37 Furthermore, Vietnam does not take part in key types of security cooperation that the hedger states undertake: it does not participate in CARAT nor conduct naval passing exercises or cross-servicing to facilitate ship visits, joint exercises, or emergency response.

Thus, while Vietnam may have moved into the edge of the hedging group, it is likely to remain a relatively weak hedger, assiduously activating its dual-track alignment options only when under duress. Its leadership, especially the older generation, “still fears the subversive intent of the United States” and is unwilling to trade Vietnam’s autonomy for risky permanent alignment with an offshore power.38 Even with inter-generational leadership change, historical experience and geo-demographic realities suggest the high likelihood that “interactions between China and Vietnam will never be on equal and reciprocal terms”39 To safeguard its imperative of autonomy, Vietnam will have to give priority to restraining China without making it impossible to live with, while borrowing US deterrence without becoming dependent upon it.

Similar deep-seated constraints will be felt, and to an even larger degree, by Myanmar, the other country in this group that has significantly changed its prospects for strategic positioning between China and the United States Under military rule following 1988, Myanmar was forced to compromise its foundational foreign policy principle of neutralism when western sanctions pushed it deep into China’s orbit. This strategic straightjacket did not ease until 2009, when the Obama administration signalled its readiness for more pragmatic engagement with Naypyidaw. The post-2010 transition to a nominally civilian regime under President Thein Sein opened up Myanmar’s strategic options. The change in US policy dramatically altered its strategic portfolio by, in turn, enlivening multiple political and economic options. Apart from high-level leadership visits, Washington lifted most sanctions and removed obstacles to UN and international financial institutional funding for Myanmar; signed a bilateral Trade and Investment Framework Agreement; and started limited military exchanges and cooperation. New opportunities also opened with American allies: for instance, Japan forgave all of Myanmar’s bilateral debt and promised significant new assistance and USD 504 million in loans.40 The resulting wider rebalancing of Myanmar’s external relations has lifted Myanmar out of its previous extreme dependence on China.41

The new US Myanmar policy is focused on promoting democratic governance and national reconciliation, and is likely to remain so for some time as the country continues to struggle with democratization and a national ceasefire with rebel ethnic groups. The bilateral defense relationship starts from a non-existent base and remains subject to the Myanmar government’s implementation of promised reforms.42 Yet, small steps like the beginnings of a defense dialogue focusing on human rights, the rule of law, and humanitarian assistance, or the invitation to a small group of tatmadaw officers to observe the humanitarian and disaster relief components of the 2013 and 2014 Cobra Gold military exercises appear more significant alongside other strengthening regional US security partnerships. On the Burmese side, ex-president Thein Sein’s willingness to offend Beijing by postponing the controversial Chinese-funded Myitsone Dam project in 2011 coincided with the US opening, and policy analysts now openly discuss using the US relationship to counter Chinese influence.

While Myanmar has bought significant new room for maneuver between China and the United States, it is very unlikely to move towards alignment with Washington. Not only does China remain a contiguous neighbour, Naypyidaw requires Chinese cooperation to manage and resolve the violent ethnic conflicts at the border. China is also heavily invested in Myanmar, in terms of commerce, migration, and infrastructure buildingㅡnot least important, pipelines constructed to transport oil and gas from Burmese fields in the Bay of Bengal to China’s Yunnan Province. China remains the most significant supplier of military hardwareㅡincluding modern frigates, main battle tanks, armored personnel carriers, artillery pieces, aircraft, and missilesㅡto the tatmadaw, despite deteriorating bilateral relations in recent years.43 Above all, Burmese leaders are unlikely to trade alignment with the United States for Myanmar’s main gain from recent changes: the possibility of recovering its traditional neutralism, staying above the fray of great power conflicts that have engulfed it at various historical junctures.

Conclusion

Over the last decade, there have been four notable trends in Southeast Asian strategies towards the United States and China: 1) more pronounced differences have emerged within the two groups at the extremes of the spectrum, the US allies and the China-constrained states; 2) the number of states that might be thought of as hedging has grown, consolidating the claim that hedging is the most widespread strategy in the sub-region; 3) the hedgers have significantly strengthened their “bets” on Chinese aggression in the short-run and have intensified elements of their insurance policies, including US security cooperation, in order to deter China; and 4) the median point on the sub-region’s alignment spectrum has moved toward the United States.

The Southeast Asia case bears out the expectation that hedging is the preferred optimum strategy for non-great power states;44 the key determinant of success is the extent to which individual states can cultivate the necessary opportunities to place multiple bets and buy multiple insurance policies. In the past ten years, hedging has come to prevail even more than before in Southeast Asia because two key transitional statesㅡVietnam and Myanmarㅡhave managed to create such opportunities. Qualitatively, hedging behavior has deepened. Despite the post-2011 trend of tilting towards the United States, the broadening modal group of hedgers has kept open their options for good relations withㅡand even future relative tilts back towardㅡChina. Even as they have emphasized short betting (by supporting the US rebalance directly and via security ties with US allies), the hedgers are still trying to tackle the question of the long bet (how to socialize China). They can also be expected to engage in more diffuse long betting, cultivating security relations with India and other major powers.

There is no wholesale turn towards zero-sum alignment with the United States. Even the two US allies have not proved themselves willing to sustain persistently enthusiastic exclusive alignment. After the Cold War, the vagaries of domestic politics have caused Manila to blow hot and cold on the alliance, and upcoming elections this year may well bring forth a new government with a different balance of attitudes towards the two great powers. Thailand has tended to wear its US alliance lightly when it comes to China, and the constraints faced by the current military regime will facilitate its straddling of the aligned/hedging boundary.

Hedging remains a popular and fairly effective strategy for Southeast Asian states because its vital purpose is to ensure “live” alignment options at each end, so as to facilitate mobility along the spectrum as and when necessary. Hedging is also a fundamentally dynamic strategy. In the short term, hedgers may seem like they are leaning more one way; however, they will continue to preserve viable strategic options in the other direction. Overall, hedgers undertake constant adjustment to try to achieve the overall effect of equidistance between two competing great powers. The implication for analysts is to refrain from drawing short-term conclusions, and to study hedging strategies across a time frame sufficiently significant for aggregating these adjustment trends.

1. Patrick Cronin, et al., “Tailored Coercion: Competition and Risk in Maritime Asia,” CNAS Report, March 2014; You Ji, “Deciphering Beijing’s Maritime Security Policy and Strategy in Managing Sovereignty Disputes in the China Seas,” RSIS Policy Brief, October 2013.

2. Evelyn Goh, Meeting the China Challenge: The US in Southeast Asian Regional Security Strategies, Policy Studies Monograph 16 (Washington DC: East-West Center, 2005), 2.

3. As distinct from what I would term “dyadic hedging”—for instance how a particular state manages its relationship with a resurgent China—, which tends to focus more on the relative mix of betting on short versus long odds, or short-term versus long-term likelihoods. For a good application of this dyadic concept of hedging, see Øystein Tunsjø, Security and Profit in China’s Energy Policy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013).

4. Darren J. Lim and Zack Cooper, “Reassessing Hedging: The Logic of Alignment in East Asia,” Security Studies 24 (2015): 696-727, 703.

5. For a contemporary analysis comparing the hedging behavior of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, see Cheng-Chwee Kuik, “Variations on a (Hedging) theme: comparing ASEAN core states,” in Gilbert Rozman, ed., Joint US-Korean Academic Studies 2015.

6. See Evelyn Goh, “Southeast Asia’s Evolving Security Relations and Strategies,” in Saadia Pekkanen, John Ravenhill and Rosemary Foot, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the International Relations of Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

7 Calculated using data in constant 2011 US dollars from the 2014 SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. Total South East Asia figures used exclude data for Laos (which were incomplete) and data for Myanmar (which were not available) for this period.

8. Renato Cruz de Castro, “Philippines and Japan strengthen a twenty-first century security partnership,” AMIT Brief, December 17, 2015, http://amti.csis.org/philippines-and-japan-strengthen-a-twenty-first-century-security-partnership/.

9. Since 2005, only three CARAT exercises with the Philippines have not been held in the SCS: the 2007 and 2012 exercises were conducted in Mindanao, and the 2009 one in Cebu.

10. “MOA allows historic PH-Japan maritime exercises,” Rappler, June 23, 2015, http://www.rappler.com/nation/97228-japan-philippines-training-exercises.

11. The ECDA’s implementation was delayed by various senators opposing the Executive Agreement’s constitutionality, but this was upheld by a Philippine Supreme Court ruling in January 2016—“SC upholds constitutionality of EDCA,” The Philippine Star, January 12, 2016.

12. “US Navy edges back to Subic Bay in Philippines – under new rules,” Christian Science Monitor, November 12, 2015, http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Asia-Pacific/2015/1112/US-Navy-edges-back-to-Subic-Bay-in-Philippines-under-new-rules.

13. De Castro, “Philippines and Japan.”

14. “Senate Oks Philippines-Australia Pact,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, July 25, 2012, http://globalnation.inquirer.net/45275/senate-passes-visiting-pact-with-australia-on-3rd-reading.

15. “Singapore says TPP vital for US to be taken seriously in Asia,” Reuters, June 15, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trade-singapore-idUSKBN0OV2NF20150615.

16. Benjamin Shreer, “Moving Beyond Ambition? Indonesia’s Military Modernization,” ASPI Strategy Report, November 2013.

17. “Military Spending in South- East Asia: Shopping Spree,” The Economist, March 24, 2012; “Hagel announces deal to sell US helicopters to Indonesia,” DoD News, August 26, 2013.

18. “Indonesia eyes regular navy exercises with US in South China Sea,” Reuters, April 13, 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-us-southchinasea-idUSKBN0N40O320150413.

19. Celin Pajon, “Japan’s ‘smart’ strategic engagement in Southeast Asia,” The Asan Forum 1, no. 3 (2013).

20. Cheng-Chwee Kuik, “How Do Weaker States Hedge? Unpacking ASEAN’s Alignment Behaviour towards China,” Journal of Contemporary China (forthcoming 2016); “Malaysia risks enraging China by inviting US spy flights,” The New York Times, September 14, 2014, at http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/14/world/asia/malaysia-risks-enraging-china-by-inviting-us-spy-flights.html?_r=0

21. Scott Bentley, “Malaysia’s ‘special relationship’ with China and the South China Sea: not so special anymore,” The Asan Forum, Vol. 3, No. 4 (2015).

22. “ASEAN defense chiefs fail to agree on South China Sea statement,” Reuters, November 4, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-asean-malaysia-statement-idUSKCN0ST07G20151104.

23. Note that Indonesia agreed to a comprehensive partnership with the United States in 2010, followed by Malaysia in 2014.

24. Cheng-Chwee Kuik, “Malaysia Between the United States and China: What do weaker states hedge against?” Asian Politics & Policy 8, no. 1 (2016): 155–177.

25. “RI, China’s navy to hold joint military exercise,” Antara, December 16, 2013; ‘‘Chinese warship arrives at Batam Island for ‘Komodo’ exercise,” China Military Online, March 28, 2014, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/DefenseNews/2014-03/28/content_4500820.htm.

26. “China, Malaysia start first joint military exercise,” Global Times, September 18, 2015, http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/943289.shtml.

27. “RI rejects joint drills in SCS,” Jakarta Post, October 20, 2015, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/10/20/ri-rejects-joint-drills-scs.html.

28. Natasha Hamilton-Hart and Dave McRae, “Indonesia: Balancing the United States and China, Aiming for Independence,” United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, November 2015, 14.

29. Goh, Meeting the China Challenge, 22.

30. “Vietnam commissions two new subs capable of attacking China,” The Diplomat, August 6, 2015; “Vietnamese submarine patrols South China Sea,” Reuters, December 17, 2015.

31. “Vietnam Builds Naval Muscle,” Asia Times, March 29, 2012.

32. “Dempsey building trust in Vietnam visit,” DOD News, August 15, 2014.

33. Bill Hayton, “Vietnam and the United States: An Emerging Security Partnership,” United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, November 2015, 25-26.

34. “Japan to give Vietnam boats, equipment amid China’s buildup,” Bloomberg, September 16, 2015, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-09-16/japan-to-give-vietnam-boats-equipment-amid-china-s-buildup.

35. Carl Thayer, “The Tyranny of Geography: Vietnamese Strategies to Constrain China in the South China Sea,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 33 (2011): 348-369, 362.

36. Hayton, “Vietnam and the United States,” 14-16.

37. “US asks Vietnam to stop helping Russian bomber flights,” Reuters, March 11, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-vietnam-russia-exclusive-idUSKBN0M71NA20150311.

38. Hayton, “Vietnam and the United States,” 22.

39. Cheng Guan Ang, “Vietnam-China Relations since the End of the Cold War,” Asian Survey 38 (1998): 1122-1141, 1140.

40. “Japan boosts aid to Burma during PM Abe’s visit,” BBC, May 26, 2013.

40. See Jurgen Haacke, “US-Myanmar Relations: Developments, Challenges and Implications,” in David I. Steinberg, ed., Myanmar: The Dynamics of an Evolving Polity (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2015), 289-318.

42. David I. Steinberg, “Myanmar, When ‘Backsliding” is a Matter of Interpretation,” Nikkei Asian Weekly, January 8, 2015.

43. Jurgen Haacke, “Myanmar and the United States: Prospects for a Limited Security Partnership,” United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, November 2015, 12-13.

44. Evelyn Goh, “Understanding hedging in Asia-Pacific security,” Pacnet 43, August 31, 2006; Lim and Cooper, “Reassessing Hedging,” 702.

EMAIL

EMAIL  LIST

LIST

SHARE